Propaganda Film and Soviet Montage

In this section, we’ll be visiting the first known film school, based in Moscow, in the former Soviet Union during the 1920s. This was known as the film movement of Soviet Montage. The first student filmmakers in the Soviet Union didn’t have a lot of access to filmmaking equipment in 1919, so they learned how to create meaning by editing film that had already been shot. This allowed for experimentation and formed the art of montage editing, which we’ll explore in this section. As with any artist, they had plenty of reasons to create their art and used it to express political opinions and influence people to change their views. The filmmakers in the Soviet Union, such as Sergei Eisenstein, realised that the audience would make their own associations between the images and sound and make sense of them to bring about their own interpretations. Though joining together “juxtaposing” images and even sounds, the audience would find meaning. This knowledge of the influence of film was used by political leaders in the Soviet Union, and later by the Third Reich in Adolph Hitler’s Nazi German regime. Either way, film is a powerful force to change the world, for better or for worse.

Marxism and Revolutionary Filmmaking

When looking at art, it is always important to consider the context in which it is created (as well as the context in which it is being viewed, published, copied etc). The films of the 1920s in Europe, particularly the Soviet Union, were often concerned with the political and economic context of the day. In this section, we will be able to consider the influence of Karl Marx, and Max Engels, who created “The Communist Manifesto” around half a century earlier in 1848. Their philosophy, known only as Marxism (the first author cited always gets the credit) would define the struggle between the working classes and the ruling classes in society. Literature, visual art and theatre had long been a medium in which the lower classes could speak out against those who held the power, and Film art was a new, powerful way in which to be heard.

In the late 1800s, we’ve seen that the Industrial Revolution gave rise to machines and great technological advances. This included the role of machinery in the workplace, undertaking the production of goods, which is something that might previously have been done by manual work. We have seen this previously in the German film industry, see Metropolis in particular for an example of film reflecting upon the struggle of the working class, though in this story the revolution was a failure. (Leigh, 2013:17)

Even before the industrial revolution, the divide between the ruling class and working class was a huge concern for people in society. In the 1800s, the people of the Soviet Union were some of the most impoverished working classes. Until the middle of the century, common people had worked on land owned by a minority of rich landowners, in medieval traditions. However, when the industrial revolution transformed production, many people moved to the cities where living conditions were poor. (History, 2018). This led to an uprising, influenced by the ideas of Marx and Engel and seeing to it that their predictions became reality. In 1905, protestors were mercilessly shot by the country’s national army, loyal to the country’s leader, the Czar. This was known as the Bloody Sunday massacre and served as inspiration for one of the most famous Soviet films of all time, Battleship Potemkin.

Audience Response in Context

The ideology of Marxism is not just limited to this historical time period. The notion that the ruling classes exploit the labour force is a common theme and one that we will return to in the Realism chapter. In any case, film always has the power to influence the audience, especially if it is based within their context. Christine Etherington, in her excellent book “Understanding Film Theory” (Etherington, 2011) offers insight into the phenomenon of audience response under the heading of the “hypodermic needle effect”,

As we cover in our first chapter, the Origins of Film, the filmmaker's art and the audience message interact to produce meaning. What the audience takes from a film depends on their reception or spectatorship theory. The idea that an audience will just absorb the message is likened to that of a needle, injecting the ideas. It is worth reflecting on whether or not this is true, in different cultures and different time periods, and for different individuals.

The World’s First Film School

The early soviet filmmakers meticulously studied the art of editing film. The Commission of Education was formally in charge of film production and controlled what was made and what was shown in the Soviet Union. Due to the impact of World War I, resources were scarce and the Commission of Education limited the amount of film stock made available (Clarke, 2011). As a result, filmmakers had to be creative with the resources they had available.

At the Moscow Film School or VGIK, students and professors would cut up and re-edit existing films and footage. The school’s founder, Lev Kuleshov, made documentaries during the civil war and in 1919, he founded the school and started the world’s first film course. Even today, it’s worth going back to study his classes, which help us to understand how meaning is created when footage is joined together. These lessons will cover some of the foundations in filmmaking through the elements of editing:

Pace

Rhythm

Juxtaposition

The Kuleshov Effect

Ideological Montage

Following the Lev Kuleshov film course, these areas of montage theory should give you a few opportunities to cut existing (or new) footage in interesting ways.

Montage Theory - Pace and Rhythm

Firstly, the art of editing is concerned with the speed in which clips are shown to the audience and the feeling that this creates.

Slow Cutting

Slower cuts, or long takes, can be used to introduce realism to the film, since in reality an individual's perspective on events does not cut. Very long takes might introduce calmness. But aside from long takes, slower cuts and cuts in classic hollywood cinema, can be conventional, standard or normal. The length of cut is usually determined in relationship to continuity editing, discussed in relation to DW Griffith’s work in the Origins of Film - it is designed to make the filmmaking process invisible to the audience, so that they don’t notice it.

Fast Cutting

In terms of pace, as we have seen in Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, speeding up the edit can give a frantic feeling to the scene. It also gives little time for audience members to process the images, making it more likely that they will take the feeling from the image in a more immediate or visceral manner, rather than processing it in an analytical way. This is often used in contemporary films to flash a few frames of film showing a character’s interior psychological state,

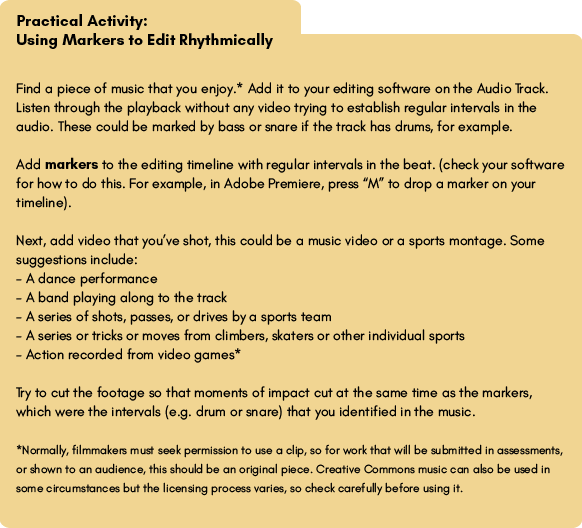

Rhythm

Similarly to pace, rhythm can set the tone or feeling for the edit. Shots cut in regular intervals, to a predictable rhythm can create a sense of stability, while random, disruptive rhythm can create discord and a sense of unease for the audience. In terms of sound design, where music is involved, editing the film to cut with the timing of the music (or against it) can be crucial to the feeling that it invokes in the audience.

Montage Theory - Juxtaposition

One of the activities that occupied students during Kuleshov’s course was re-editing existing films. One film that they would focus on re-editing was the epic masterpiece “Intolerance” by American filmmaker DW Griffith. The work of DW Griffith was extremely popular in the Soviet Union (you can learn more about in the Origins of Film chapter, or watch the short film “The Lonedale Operator” in the Film Library). Intolerance was shown throughout the country at the behest of the Soviet government leader at the time, Vladimir Lenin, who commended it’s “scope and purpose” (Moma, 2019).

The idea of rearranging the clips from existing films was based on the understanding that the film clips, when joined together, create meaning. See figure below.

The Kuleshov Effect

One of Lev Kuleshov’s most famous experiments exemplifies the Ideological montage - or joining together of two clips in order to create meaning. He proved that the image of someone’s face looking past the camera can be connected to almost any other image and that the audience will assume that the person is looking at whatever is in that image.

To demonstrate he took images of a bowl of soup, a coffin, and a lady. He cut them inserted between images of a mans face staring with a neutral expression.

A test audience was questioned on the meaning in each case. The experiment apparently showed that audiences perceived the man as hungry, sad and lustful with relation to the soup, coffin and lady respectively. This is despite the fact that the same shot of the mans face was used in all three edits!

This technique was reiterated by Robert De Niro in an interview when he said about his process “Actors can at time’s think you have to give it something. You don’t have to give it anything”. In fact many great actors from Robert Redford to Ryan Gosling have in their own way, explained this effect. Try searching for “Ryan Gosling stares: for fan montages as proof.

This understanding, as further outlined by Sergei Eisenstein, demonstrated that new meaning could be created by the assembly of two film clips.

This is just one of the ways in which editing can create meaning as well as pace, rhythm and juxtaposition.

Activity: Reordering a storyboard. The juxtaposition, (or joining together of two things for contrast) of film clips can lead to inherent meaning when the clips are shown. In the example below the house followed by the room might indicate that the ROOM IS IN THE HOUSE (change according to the images used)Look at the storyboards below. Storyboards are graphic illustrations used in pre-production to plan how the film will be assembled. They are a great tool for the editor to use when planning how to join clips together, whether they are going to create contrast in juxtaposition, or trying to match one shot to another. Try to reorder the images to create a new meaning. What was the original meaning?What did you change?How does this create new meaning?

Activity: Ideological MontagePure ideological montage like in Battleship Potemkin. Try using the Kuleshov effect as a part of it. Activity: Alternative Endings/Deleted ScenesHave you ever watched a film that you liked, but hated the ending? Or did a character (or actor) ruin a scene for you? As an extension to the activity above try reediting a scene of a film to change it. You might be surprised how often this happens in post production. Check out the bonus material on your favourite films extras for examples. Activity: Mash UpAlternatively, you can intercut two films (which could be easiest if they are the same genre, in order for the visual style to be consistent). You might be able to create a whole new story. Short Film In this topic, create a short film or scene. Use quick cutsEstablish rhythmYou must create storyboards