Silent Film

The Roaring 20s.

The silent film era took place in the USA, with the emergence of Hollywood as a centre of film production. Business was booming at the turn of the 20th century in the US, with manufacturing and industry learning processes and techniques to churn out products. In the motor car industry, take the Ford Model T for example, introduced in 1908, made on a production line. But textiles, mining and agriculture all went under similar changes in the Industrial Revolution in the US, and Film was no different.

Soon, filmmakers began to create and distribute film all across America and abroad. Due in part to these changes, the US economy began to grow, during the “roaring 20s” average household income increased and people were able to afford regular visits to the cinema, which had grown in popularity since the beginning of the 20th century.

D W GRIFFITH

One of the most influential filmmakers of the era was David Wark Griffith. D.W. Griffiths work would come to influence filmmaking around the world, thanks to his creative use of the camera and editing techniques. Soviet and German filmmakers would later watch films by D.W. Griffith and borrow these techniques, such as the close up shot, continuity editing and intercutting back and forth between parallel action.

That isn’t to say that he was the only filmmaker of the time using these techniques, only that he was known for mastering them. Besides which, the films he made, such as The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916) and were some of the most widely watched films of all time. The filmmaking is innovative, but the messages in Birth of a Nation were insidious, including glorification of the racist Ku Klux Klan. Intolerance has somewhat redemptive themes for Griffith, it’s purpose to show instances of intolerance through the ages. This film even contributed to incite revolutionary filmmaking in the Soviet Union and was liked by Lenin, who had it shown throughout Russia after the 1917 revolution, to support the uprising.

In any case, it is D.W. Griffith’s aesthetic that endures and his techniques that hold him in high esteem. To examine this in more detail, we can look closely at one of his earlier, less thematically encumbered, short films. The Lonedale Operator.

The Lonedale Operator (1911) D.W Griffith

In the early days of cinema the audience was used to seeing theatrical performances in traditional format on a stage.

It was thought by filmmakers that if the camera moved to an unusual perspective this would be jarring. That means that if the camera showed the audience an angle they wouldn’t normally see, they were worried that this would seem too strange and the audience would lose interest in the film.

That didn’t stop D.W Griffith playing with different angles and shot types. His work was recognised as instrumental in establishing the new conventions in film. In fact, Charlie Chaplin called him “the teacher of us all.” (1)

In the Lonedale Operator the close up is used almost as a visual gag, but nonetheless, shows how natural it is to get close and focus in on an object, the same way that our attention would be drawn to it in real life.

This insert shot is intended to reveal the ‘gag’ that she is not holding a gun, as it first would seem.

There are many different Shot Types but several are used commonly:Extreme Long Shot (and establishing shots)Long Shot (and medium long shot)Medium Shot (and medium close up)Close Up (and extreme close up)

Establishing Shot

A wide shot of a location that establishes a sense of environment and surroundings. It is usually the first shot of a new scene and is designed to give the audience and impression of where the action will be taking place.

Extreme Long Shot (XLS)

A wide shot that places a person or object a long distance away from the camera. This shot emphasizes the size of the character compared to the landscape such as skyscrapers.

Long Shot (LS) or Wide Shot (WS)

A shot in which a person can be seen from head to toe. The character in the shot takes up almost the full frame height. The long shot is also used to determine the surrounding environment in the scene.

Medium Long Shot (MLS)

A shot in which a person can be seen from the knees upwards. A medium long shot shows the subject in relation to the surroundings.

Medium Shot (MS)

A shot in which a person can be seen from head to waist. Medium shots are to show the characters body language in the context of their facial expression.

Medium Close Up (MCU)

A shot in which a person can be seen from head to shoulders/ upper body. This shot is commonly used when characters are having conversations

Close Up (CU)

Close ups are shots usually of the characters face used to show emotion or activity they are doing with their hands. Close ups allow the audience to connect emotionally to the character.

Extreme Close Up (XCU)

A shot which captures a specific feature or reaction on a person’s face. The shot is usually so tight that only certain details such as someone's eyes or mouth can be seen.

With examples from a Silent Film of your choice, take screengrabs and label the shot types. (Silent Film era is around 1905-1925 and if you prefer, you could focus on the work of D.W. Griffith). By setting the stage as far or as close (or as wide or tight) as needed the language of film can be more flexible than theatre. What filmmakers discovered was that rather than breaking the illusion for the audience moving the camera to capture what is important on screen was actually more immersive.

This means that film gave audiences the opportunity to see the level of detail (or breadth of the scene) as they would if they were actually there. Take for example when looking at someone's face, it’s their features that are taking up most of the observer's attention rather than the objects in the background. So it makes sense when filming someones face to use a close up, showing the audience only that which is most relevant.

Using Shot TypesCreate a very short scene (eg. Entering late for class) with at least 5 shots to show us a character.Rubric•1 Extreme Long Shot/Establishing shot•1 Long Shot/Medium long shot

•1 Medium Shot•1 Close Up•1 Extreme Close-upTry planning your simple scene by thinking about what the Extreme Close Up/Close up will be… this will probably be the key shot (just like in the Lonedale Operator)•Get ’coverage’ of your scene.•Do a maximum of 3 takes of each shot.You’ll need to film the whole action - everything that happens in the scene - from each angle. That means do the whole thing from the wide angle, then do it again for the medium shot, then again for the close up. (You might be able to get away without doing the whole scene for the close up).

The Invisible Art

D.W. Griffith also used a number of techniques, perhaps intuitively, that would later be copied by many filmmakers. The aim was to hide the cuts in the editing process of joining different shots together. This led to film continuity editing being called “the invisible art”. In order for the edit to be successful you will need to bear these in mind as a director.

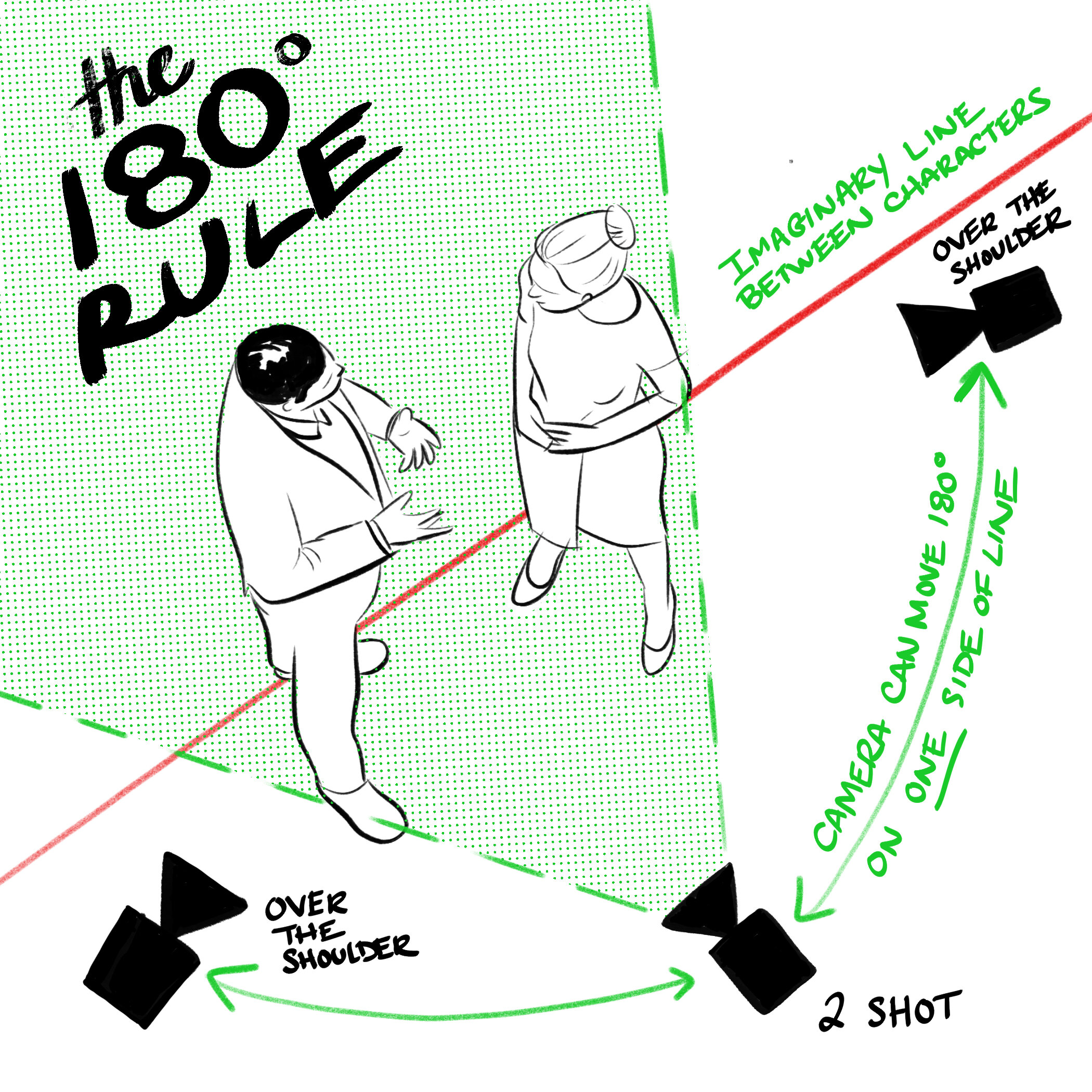

180 Degree Rule

Shots should always be kept to the same side of an imaginary ‘action line’. Otherwise the subjects appear to reverse positions on the screen.

30 Degree Rule

The 30 degree rule states that you should move the camera position AT LEAST 30 degrees from the previous position used. Otherwise the shots will appear too similar, even if they are at a different focal length or zoom level.