WELCOME TO A WORLD OF FILM.

Film has not existed for a long time compared to other forms of artistic expression. Consider the thousands of years of Theatre, Music, Dance, Painting and Sculpture throughout recorded human history. Each one offers a different medium which people have used to communicate meaning for Millennia. Film, by comparison, only arrives late in the 19th Century, yet has quickly grown alongside technology, globalisation and the age of information to be a method of communication to a collective and captive audience of billions. Film and Television are one of the most popular and profitable pastimes. In terms of the amount of film watched in Cinema, the Global Box Office sales worldwide amounted to $38.8 Billion USD in 2016 and is growing1. Television and Internet Programming increase the consumption of Film even further, with Netflix, YouTube and others have audiences watching up to five hours per day2. The love for Film transcends culture whether it’s made in the North America, the UK, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Japan, China, South Korea, India, Iran, Russia, Senegal or Nigeria, people are watching and sharing stories. Stories have always been with us. Film has simply allowed humans to tell the story in a different way - and perhaps one closest to our own original experiences.

THE ART OF FILM

Film might be a relatively recent artform, but it takes many aspects of storytelling from the other Arts disciplines. Instead of a painting, film has a moving image. Music scores enhance the feeling in film, actors often move like dancers, the stages on which the film is set contain the sculptures. It is a multi-disciplinary art form and by necessity, is a collaborative artform where a number of people can bring their skills and talents to the final product. Acting, Sound, Cinematography involving Light and Camera are but a few of the roles that combine to create a successful motion picture. The result is a work of art that communicates to the range of human senses and emotions. It is no wonder that it captivates the attention of so many people, in so many places, for so much time. It is a close proxy for real experience - Film looks, sounds and feels closest to our lives, if not, our dreams.

Painting with Light The term Photography, from Greek phōtós-graphê literally means Light-Drawing. With the invention of cameras, which are simply machines that focus and control the light onto sensitive material, artists were now able to paint with light.

The Camera Obscura The idea of capturing light dates back to the 11th century in Persia, with what became known as the camera obscura, created by Ibn al Haytham. This is simply a box with a tiny hole, through which light can pass and display an image.

In the 1800s it was discovered that by exposing certain materials to light, they would react and leave an impression of the thing that the material was exposed to. Photography built on the concept of the camera obscura to project the light onto the photosensitive material by using a lens to bring the light into focus and create still images representative of the subject. This was known as heliography - literally translated as ‘writing with the sun’. By the close of the 19th Century, further ingenuity and invention allowed for the capturing of a series of photographs in quick succession and this is how Film was born.

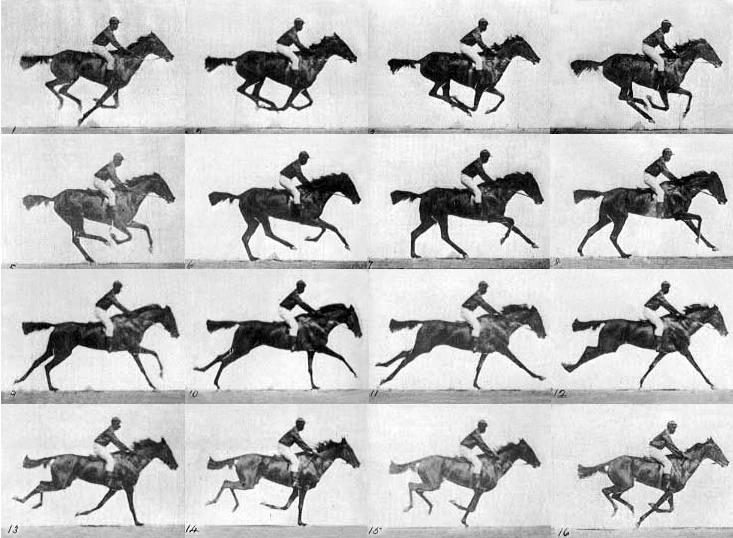

Zoopraxiscope

Created by Eadweard Muybridge in 1879. The zoopraxiscope projected images from rotating glass disks in rapid succession to give the impression of motion. The stop-motion images were initially painted onto the glass, as silhouettes. Muybridge photographed a horse running to determine the outcome of a bet: that the horses legs were all off the floor at a moment in time. It was true, the horse triggered the camera by tripwires, with images clearly showing all legs to be off the ground. Muybridge was able to use this technique of multiple photos in short succession, in order to create the Zoopraxiscope. When watched quickly, the horse appears to be running.

However, this idea of quickly displaying images to fool the eye into seeing motion, it wasn’t unique or new. Chinese historical archives contain multiple inventions where images of animals and birds are projected using a lamp and translucent paper (much like what was named a Thaumatrope in the 19th Century). The heat caused the paper to spin and the quick replacement of one image following another gave the illusion of a moving subject.

The Myth of the Arrival of the Train

Perhaps the greatest myth in cinema history, The Arrival of the Train is known to be one of the first films ever to be screened to an audience. The first camera – the Cinématographe was was invented by a Frenchman called Léon Bouly and the patent was sold to the Lumiere brothers who improved on it. The Lumiere Brothers broadcast this film on Jan 25th 1896 at the Salon Indien Du Grand Cafe in Paris. They used their invention, the Cinematographe, which was capable of capturing and projecting film. This was not the first film they showed, or even the first documentary (we know of at least one prior to this when they recorded their workers leaving the Lumiere Brother’s factory). But we know that very few films had been screened at this point in history and the Lumiere brothers wanted to share their invention. We also know that the audience had most likely never seen a moving picture like this before.

The myth is told that the audience were supposedly so scared of this image of a train coming towards them, that they left their seats and fled the cinema.1 But could this be true? Experts opinions are divided on whether or not this reaction is the result of exaggerations and false reporting.

According to film historian Martin Loiperdinger “The moving images projected onto the screen with the Cinematographe Lumière could hardly be mistaken for reality," Furthermore, through his research he goes on to state "Contemporary reports of panic reactions among the audience cannot be found. The repeatedly reiterated anecdote that the contemporary audience felt physically threatened and therefore panicked must be relegated to the realm of historical fantasy."

But others have considered the possibility that the audience was so unfamiliar with moving pictures that this response might have been real. Remember the Camera Obscura from the start of the chapter? Audience might have seen Camera Obscuras in action previously, knowing that they required the subject to be actually standing behind the aperture of the camera. They might therefore have expected the train to be on the other side of the wall. Additionally, historian Ray Zone points out that the audience might have been influenced by a train crash that happened in Paris only months before on Oct 23rd 1895.

FILM JOURNALING METHODS

There are many ways to keep a journal of the films that you watch during your studies. You can produce a document using software on your computer or online using Google Docs or similar web-based programs. There are also specific websites for which you can create a journal. www.letterboxd.com is the author’s personal favourites and Groark, Ekkel and Roper can all be found there with their lists of films to watch, avid (though not always professional) reviews and example journals.

www.letterboxd.com is a personal favourite journalling site, unless your teacher has a better option.

AUDIENCE RESPONSE THEORY

There are a number of ways in which academics consider the audience response to film. It is also known as ‘Spectatorship’ or ‘Reception’ but under any title, this theory refers to what meaning is taken by the person viewing the film.

Earlier in the chapter we discussed the meaning of art. One definition might be concerned with the meaning communicated by the artist and the meaning received by audience. It can be argued that whatever the audience takes from the art is it’s true meaning. It can also be argued that there does not need to be an audience in order for the art to have a meaning that is imbued by the work and vision of the artist. Theories of Knowledge on Art worthy of discussion also consider that the ‘Quality’ of the art is worth debate as well as the meaning that is contained within it.

To give a practical example, imagine that a wood sculptor carves the image of a bear into a tree trunk. The sculptor, proud of his work, attaches a text to label it a bear. A few days later, a neighbour sees it and loudly exclaims to the artist ‘Nice Dog’! The viewer observes a different image to that intended by the artist - which is the art representing, the Bear or the Dog (or both)? Does the work itself contain specific characteristics of a bear, or a dog? Is the artist’s idea more important that the audiences? What if no one were to view it at all? This is just a simple way in which the relationship between artist and audience can be seen. The best conclusion might be a compromise that it is in fact both the artists and the audiences meaning that is valid when considering a work of art.

AUDIENCE RECEPTION KEY QUESTIONS : 5WS + HOW

When considering your research into the Audience Response, it is important to consider key questions about the film which are commonly asked in research. The first 5 begin with W:

1. Who

2. What

3. Where

4. When

5. Why

6. (How)

The 6th question, How, relates to how the work was created and how it was viewed. It is important to note that the 5 Ws and the ‘How’ are relevant to both the Artist and the Audience sides of the Art. The Audience will view the work in a different way depending on Who, What, Where, When, Why and How they view it.

The importance of Audience Response, Reception and Spectatorship can make all the difference to understanding the film’s meaning and it’s value.

For example, some films are reputably so bad, that the audience might actually want to see them just to see and laugh at how bad they are (See the work of infamous Hollywood Director

Ed Wood, or the Tim Burton/Johnny Depp 1994 film about his career). Value has been created where you might not have expected it to be found due to the poor quality of the work.

The audience members might have preconceived notions about a film depending on what genre it has been publicised to be part of, or what genre they perceive it to be. Someone going into a film they believe to be horror might be more scared in anticipation, or more disappointed if they aren’t scared, or confused if they find it to actually be a comedy (The year 2000 spoof, Scary Movie, for example).

The Who, What, Where, When, Why and How a film is both made (by the artist) and consumed (by the audience) can vastly alter the message and the communication of meaning.

Audience Size The size of the audience can also impact the perceived value of a work of art. In the example earlier with the Dog and the Bear sculpture, the fact that only one audience member had seen it, potentially led to the confusion about the meaning. If a large audience views a film and responds in a certain way, it can be said with more certainty what the meaning of the art is. In the early days of cinema the audience might have been small for each film, but with globalisation and the internet the modern day audience is much larger and often connected.

Collective Audience If the audience is also able to share their responses then the audience members might have an influence on how the art is perceived. The audience members communicate through a variety of methods including face to face, particularly if the film was viewed together, but also before and after the film has been seen. They might communicate through electronic methods on the internet such as social media or website forums and comment threads. The audience member’s opinion is therefore formed not just through reading the same critics or reviews, but also through the shared communication between audience members. This passing of information regarding the film from one audience member to another can often mean that the audience members share the same views.

AUDIENCE ACROSS TIME AND SPACE

The audience response might be different depending on the time or place in which they consumed the art. An audience member in the year 2010 watching a film that was released in 1940 will have a very different current context in which they are living. Their current context will contain certain expectations and norms that will influence the way in which they see the work.

Similarly someone living in a different country to that of the films origin might view it with reference to their own culture and interpret the meaning differently. A film made in a developing country will have different Political, Economical, Geographical, Technical, Historical Institutional and Social contexts and therefore the understanding of what the filmmakers and artists intended might be seen differently. In addition, a film seen in a different context, place or a different time can be received by the audience very differently. This can be seen, for example, in ‘cult classics’ such as Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), which did not receive a great deal of praise from critics, or popularity with audiences at the time of it’s release, but has since been regarded as one of the greatest films ever made, with a popular following that led to a 2017 remake hoping to gain further popularity with audiences.

Conclusions

The value of the art is subjective and will be appreciated differently by every individual that consumes it. This value might relate to the qualities and characteristics of the artwork, in this case the film, but every person who sees it will judge it differently for themselves, depending on the way they see it due to their own knowledge, experiences and cultural context.

The way that the audience member makes this judgement also depends not only on their own understanding and perception of the message communicated by the artist, but also on the influence of the collective audience, who will communicate via word of mouth and published sources of information such as newspapers, books, articles, forums and critic reviews.

The views of the audience can and will change over time and space. Films viewed by a member of the audience in one time period might not be perceived in the same way as those in another geographical location, in a future time. The meaning communicated by the film can therefore be seen very differently when viewed by an audience in another time, place or cultural context.

What this means for the film is that it’s message, value, meaning and even its quality can be seen to change, depending on the audience reception.

Do you think the audience opinion is more important than the intention of the artist in creating meaning in Film? Evaluate both sides of your argument and justify your conclusions

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

The invention of Film, as we have seen, is a late development in the art world. It’s original form was the product of a series of inventions that were the product of a cultural curiosity and creativity during a period known as the Industrial Revolution, spanning the 18th and 19th century.

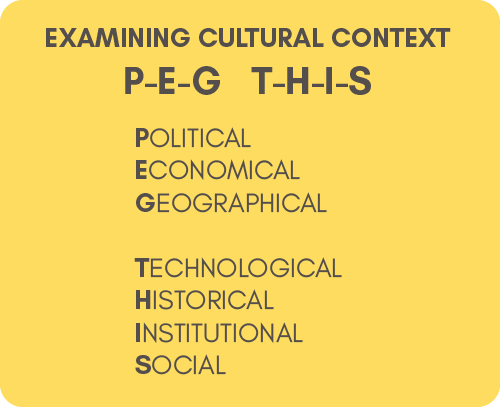

EXAMINING CULTURAL CONTEXT

It is essential therefore, when considering Art, to look at the context. The cultural context comprises a range of influences on the artist.

One way to remember the Cultural Contexts of a work of art is with the mnemonic PEG THIS.

Political A film might be influenced in story, theme or subject by the political context, but might also be directly impacted politically by censorship, where filmmaking or distribution is restricted. A film might even be created and distributed for spreading a political message.

Economical Economic influences on Filmmaking are concerned with the amount of money available to both the filmmaking industry and to individuals in the broader cultural context. The economics of filmmaking can be influenced by funding, grants and tax related benefits for filmmakers. The broader context of economic influences might influence the subject of the film, which will be situated within the economic context of the country and it’s individuals - richer or poorer.

Geographical The location of the film can determine how a film is made - even if you don’t consider the social, political, historical and economical context. Films might represent that country, language, people and the view of the world differently. The traditions of a country can be very important too in determining the artistic choices in the filmmaking process and the subject of the film.

Technological It is important to examine any Art through the Cultural Context. For example, In the Origins of Film, we have looked at how the Technological advances lead to the birth of the Film Camera - although we could have gone into more detail examining the process of recording light and the types of materials and devices that were used.

Historical Historical events can also have a bearing on Art; the actual historical events that might inspire Film. While the invention and the exhibition of Film is a historical event itself, a clear historical example would be the Photographs of the launching of the Titanic in 1912. Towards the end of this book you will see how Filmmakers went back in time to recreate this event on Digital Film in 1997.

Institutional The institutions, businesses and organisations that create films have an influence on what they are and why they are made.

Social Another important cultural influence on the origins of film was the Social context - where we have discussed the culture of curiosity and ingenuity. Socially it was an age of invention, people would spend time and energy using their education to discover what was possible. This was reinforced by the speed of progress that was evident all around them.

It is important to remember whatever the type of context or whatever the art form, art can always be viewed and should be considered in relationship with the context in which it was produced. Who made it, why they made it and who they made it for, is essential thinking for understanding the meaning that is being communicated and received in Film.

Short Film: A Journey to the Moon

A Journey to the Moon is often regarded as the first Sci-Fi film1. It is about the engineering of a huge gun powerful enough to propel a capsule, containing scientist explorers, from the Earth to the Moon. Once there, there is some conflict with the native inhabitants and the scientists have to make good their escape - in one of the first examples of Post-Colonialism in Cinema (we will come to this Film Theory later).

The story was inspired on the 1867 Jules Verne novel “From the Earth to the Moon2” and the H.G. Wells Novel “The First Men in the Moon3” which came just a year before this film. Such was the spirit of this time period, where innovation and curiosity were celebrated in the Industrial Revolution - people were fascinated with pushing the boundaries of exploration. Since explorers had mapped and charted most of the planet by the end of the 19th Century, they looked to the outer space. However, it would be another 67 years until the first manned shuttle to land on the Moon famously landed (and was filmed and broadcast to Earth) on 20th July 1969. Science Fiction sometimes attempts to show what could be possible, such is the power of film.

The Journey to the Moon film has been highly influential. The idea of combining scientific ideas, showing the audience things which are not yet realised, is one of the most entertaining premises for a story and the Sci-Fi genre gives audiences the joy of this discovery. Often praised as one of the first narrative films, the story underpins not just sci-fi, but also Fantasy Genres and even the Road Movie.4

The stage design, is complex and storytelling is enhanced through the artistic, non-realistic portrayal of this fantasy world on the moon. The Production Design, or Art Department is heavily influenced by theatre of the time, yet this was a new innovation by the Melies brothers to bring it to the recorded art of film.

As well as inspiring other films of Sci-fi and space exploration, Journey to the Moon is embedded in popular culture, it is after all, a historic piece of cinema. From television, to music videos and of course, other films, journey to the moon is recognisable through the composite stage design and unique art style.

Task: Cultural Context Consider the Film Journey to the Moon (or other silent film). What influences can you perceive on the film from the Cultural Context (PEG THIS).

DIGITAL

Melies’ techniques were achieved by creatively using the camera to overwrite and manipulate the physical film, by winding back the camera, stopping and starting it and even cutting out the frames of the film in the edit. The same can be done digitally with modern technology by applying the same approach but without having to physically interact with a material - it’s all done within a computer.

This has also allowed for computer generated images and even further exploration using technology like Green Screens.

Hugo (2011) Martin Scorsese

Martin Scorsese is renown for his work in the Gangster and Crime genre but he is an incredibly dedicated and hard-working filmmaker. Scorsese himself is a Film student and one of the “Film Brat” generation of 1970s filmmakers who studied film.

Based on the book that pays homage to the work of the great George Melies, Scorsese has created an ode to the Origins of Film in “Hugo”. Set in Paris in the 1920s, when you watch Hugo it can take you back to a time before digital: a time of clockwork and invention. The Industrial Revolution.

Hugo is also a great film to watch if you want to see early films in context. It has excerpts of “Workers Leaving the Lumiere Bros Factory (One of the first films ever shot), the Arrival of the Train (the first film ever broadcast) and Journey to The Moon amongst others. You will see representations of the audiences reaction to seeing these new and wonderful moving pictures including the myth surrounding the arrival of the train - that the audience nearly jumped out of the way of the oncoming train on screen!

Most importantly, though, Hugo gives the viewer that sense of wonder which the original audience might have held. Trains feature in the origin of film quite often, a symbol of the steam age and in Hugo, Scorsese sets the action in Paris’s central station, further anchoring the setting by having the main character live inside the clock tower.

This love for technology is also a clever demonstration of how far it has developed in over a century of filmmaking. Scorsese chose to shoot for 3D, which is a complex process involving precise angles of filming on two cameras. Primitive 3D film had been around for a long time (for example in Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder) but was made more complex with the long moving shots in Hugo. In exploring 3D in Hugo Scorsese brings film full circle, demonstrating the latest technology to show the original film technology.

Ultimately, Hugo is the story of a boy. Perspective is always key in cinema, because our experiences are not purely robotic like the automaton in the film, but emotive. Scorsese uses this motif intentionally and purposefully as summarised here:

“It’s about how it all comes together, how people express themselves using the technology emotionally and psychologically. It’s the connection between the people, and the thing that’s missing – how it supplies what’s missing.”

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2010/nov/21/martin-scorsese-3d-interview-kermode

Choose a segment of no more than 2 minutes from Hugo and discuss the Cultural Context, with reference to the Industrial Revolution and Technology.

•What differences can you observe between Hugo and Journey to the Moon?

Example: Basically everything has changed in film over this time, so even the fact it’s in Colour.

•Remember PEG THIS but also focus on the Technological Aspect.

•Write an essay plan before you begin.

If this is the first time you’ve studied film, you might want to skip the next task and come back to it. The Melies style film is harder than the D.W. Griffith style film in the next chapter: Silent Film.

You can come back to this film later as an end of unit film once you’ve had chance to experiment with basic shot types.

Melies Style Film

roLe

If you are working in a group, describe your process for your role. Melies was a great director - but there were also other key people in the team, such as the cinematographer or the editor. Whichever role you choose, clearly define it (it might be, for example, you do costumes and set/stage design. This would be fine but you have to clearly state what you do, while making sure it’s related to Melies).

LEARN

Research the techniques that Melies used. Give examples using screengrabs and explain their process.

Be clear about how George Melies movies influence your role. Be sure to cite your sources.

CREATE

Make a Film in the style of George Melies using the following techniques:

Stop Edit

Dissolve

Masking

Create a short film of 3 minutes or less. While making the film take lots of behind-the-scenes video or photographs to explain the process and decisions you are making.

REFLECT

Evaluate your success by considering the following:

· What challenges did you encounter and how did you overcome them?

· How does your final work presented compare to Melies work with clear reference to artistic influences?

DIGITAL EXAMPLES

There are a number of modern films that use techniques similar to Melies.

The Stop Edit can be seen in Ringu (2000) Japan directed by Hideo Nakata.

Dissolve can be seen in any number of films, often as a transition.

Masking is used effectively in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) directed by Michel Gondry and written by Charlie Kaufman.

Green screen - which is essentially

Computer generated images

They’re all worth watching as inspiration for your own Melies style film. Remember, there’s nothing wrong with using narrative ideas from other films (the same as there’s nothing wrong with trying to copy the technique).

A NOTE ON INFLUENCES

At this stage, you should take ideas wherever you find them. In the end, your combination of others ideas is your own recipe for your work. Just like with any other subject, you should be learning from others work. It’s actually a good thing to be able to explain your influences and say how they informed your work. As you can see from Digital films, the same ideas can be done again, especially in a different cultural context and for a different audience.